Everything you need to know about vinyl record grooves

Run-in and Run-out Grooves

The run-in or lead-in groove is the section your needle first encounters. It doesn't carry any music, its main job is to gently guide the needle onto the record's sound-carrying grooves. It also gives your turntable a moment to get up to its correct speed and rotate smoothly. The length of this groove, usually a few revolutions, varies because turntables differ in how quickly they get up to speed.

At the end of the record side, you'll find the run-out groove which guides the needle towards the label area. This is where a turntable's limit switch, if it has one, will activate to lift the tonearm. There isn't a strict standard for where this groove is located, but it's typically between 103mm and 104 mm in diameter.

There’s often discussion about whether limit switches are necessary but there's no single answer and there are different types. Purely mechanical solutions which might restrict tonearm movement during playback and cause vibrations and optoelectronic switches which use electronics that can be susceptible to wear. Both add cost and are a trade-off for convenience. A common worry is that not having a limit switch could damage your stylus or record if the tonearm is left in the run-out groove. However, it’s generally agreed that while leaving it for hours might cause some wear and tear, it's considered negligible compared to the stylus's overall lifespan, especially because the run-out groove is very smooth.

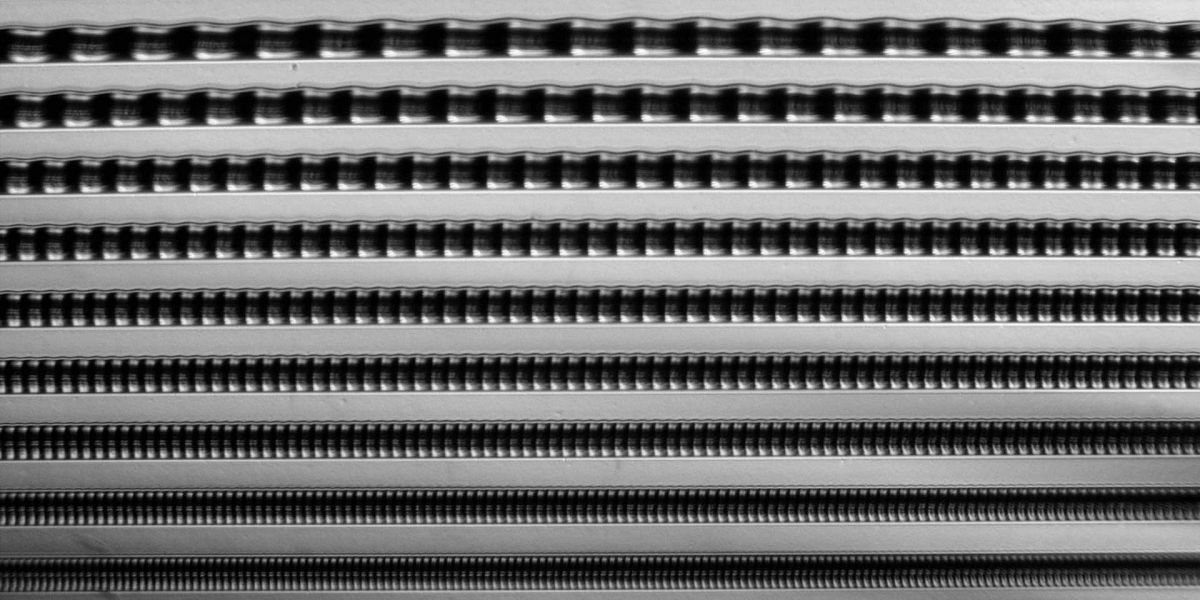

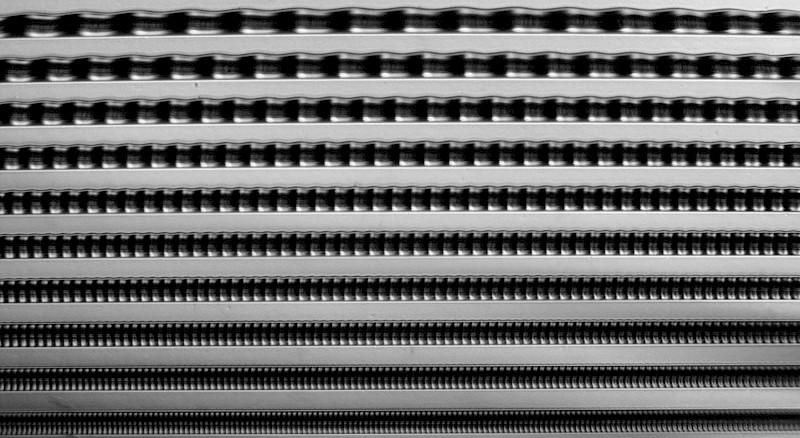

Groove Width

What about the width of the grooves themselves? The lead-in and lead-out grooves, which are smooth, are generally about 40 µm wide. This is considered an industry standard. Modulated stereo grooves (the ones with music) are also typically around 40 µm wide, while mono grooves are wider at about 55 µm or more. There are different standards for groove width, as well as for the groove rounding radius and angle, set by companies like RCA and Columbia, and German industry standards (DIN). However, these standards differ so slightly (e.g. groove angles of 90, 92, or 87 degrees with a one degree tolerance) that they don't affect whether a record can be played on different turntables.

Marking Tracks: ID Grooves

Between the different songs or tracks on a record, you'll usually see identification grooves, or ID grooves. Unlike the lead-in and lead-out grooves, these can be modulated, meaning they might contain sound. What characterises an ID groove is that it's cut so the distance between revolutions, called the "land," is slightly increased. This effect is mainly visual. ID grooves can also be placed within a song without interrupting the music.

Locked Grooves: Stuck in a Loop

A fascinating special type of run-out groove is the locked groove, also known as an endless groove. These contain sound information, and at the very end, the needle gets caught in the same groove revolution, causing a tone sequence or sound to repeat over and over. This usually happens at the end of a record side. On a standard 12 -inch record playing at 33rpm, this repeating sound sequence is almost exactly 1.8 seconds long. This is the time it takes for one full revolution at the typical run-out diameter. While the idea of creating a perfectly looping beat in a locked groove is appealing, it's technically very difficult to determine exactly where the repetition will happen during the cutting process. Achieving a perfect beat loop would require considerable skill and many attempts. You'll also often hear a characteristic "plop" sound when the loop repeats. Some records are even entirely made up of multiple locked grooves, providing different loops for DJs, particularly in genres like techno or hip hop.

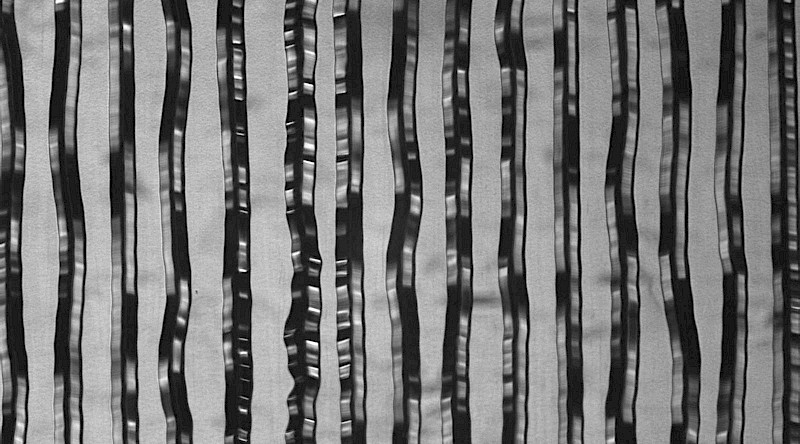

The Cutting Edge: Helix (Double) Grooves

Pushing the boundaries of vinyl cutting are helix grooves, also called double or parallel cuts. This idea is associated with the cutting and mastering engineer Ron Murphy. Known as "Motown Murphy," he became famous for mastering early Detroit techno records and developing unique approaches. He often exceeded previous limits, for example, in bass proportions, creating cuts that sometimes needed specially calibrated systems to play back correctly. He even experimented with inverse cuts, where the groove runs from the centre outwards, making them harder for bootleggers to copy. Working with Jeff Mills, Ron Murphy also developed locked grooves specifically designed to loop a beat at a precise tempo (133.3 bpm).

His NSC-X2 technology (NSC standing for his company - National Sound Corporation) involved cutting two grooves parallel to each other. This means when you place the needle down, you might land in either the first or the second groove, and two different tracks could play depending on which groove the needle follows. These parallel or helix cuts, though complex to produce, are now offered by many cutting studios, and some engineers are even developing them further. You can now find triple helix cuts (three parallel grooves) and even inverse triple helix cuts where two grooves go inwards and a third plays from the centre outwards.

Creating these types of cuts is time consuming and requires significant material. One of the main challenges is that the final length of a groove spiralling towards the centre isn't precisely predictable. The actual playing time depends on the dynamics of the audio material – its volume, loudness, and the mix of high and low tones. These factors influence the feed rate, which is how fast the cutting stylus moves along the record's radius and determines the distance between groove revolutions. Engineers try to keep the feed rate low to fit more music on the record and stay in the outer, higher-quality area. However, they must also account for strong movements of the stylus during loud, dynamic parts. If the distance between grooves isn't enough, these movements can bend the “land” (the space between grooves), leading to pre-echo, where sound from one revolution bleeds into the previous one.

With helix cuts, this challenge is doubled because the space between grooves must accommodate the second groove, which has its own dynamics. The process involves cutting the first groove, then moving the cutterhead back to start cutting the second groove right next to it. This often takes multiple attempts, leading to waste, because you might only realise near the end of the second cut that something doesn't fit, forcing you to start over. It requires not just technical skill but also, as Ron Murphy himself put it, a certain “artistic enthusiasm”. He once said, “Editing is not about music. You have to love records”.

Final Thoughts

From the simple purpose of guiding the needle to the complex artistry of cutting multiple parallel grooves, the world hidden within the tiny lines on a vinyl record is surprisingly diverse and technically demanding. These different groove types, some standard and others highly experimental, highlight the ongoing innovation and dedication of cutting engineers who are truly passionate about vinyl.

More articles from Breed

Vinyl Record Grooves FAQ

The run-in (lead-in) groove is crucial for helping the stylus settle smoothly onto the record without damaging the music grooves, while the run-out groove safely leads the stylus toward the label area once playback finishes. Together, they protect both the record and your equipment and allow turntables to get up to the correct speed before the music starts.

A locked groove is a special looped groove at the end of a vinyl side where the needle repeats a short sound endlessly. Artists and engineers use them creatively — for sound effects, hidden tracks or DJ tools — but cutting a perfect locked groove takes exceptional skill, since timing, groove placement, and sound dynamics must align precisely.

Double or helix grooves are two (or more) parallel grooves cut side-by-side on a record, so you might hear a different track depending on where the needle lands. Cutting them is highly complex because each groove must be perfectly spaced and balanced, with careful control of the audio’s dynamics to avoid crossover. It’s an art form that requires expert planning, technical precision, and often a lot of trial and error.

Cutting Vinyl Record Grooves With Breed Media

At Breed Media, we know that great vinyl starts with great grooves. With over fifteen years of experience, we’re experts in every detail of vinyl cutting from the lead-in groove to the most complex helix cuts. We treat every master with the same care and precision as if it were our own, making sure your music sounds its absolute best on vinyl. Whether you’re creating a classic album or pushing the limits with locked grooves or parallel cuts, our team is here to guide you through the process and protect the integrity of your sound. When you work with Breed Media, you can be confident your record is in the best possible hands.